Recently, IBM announced the fabrication of the 7nm node, packing transistors about four times as dense as current technology, surprising you and me both who thought that IBM didn't make things anymore. IBM had just paid semiconductor behemoth GlobalFoundries 1.5 billion dollars to take its (IBM's!!!) fabrication plants (Fabs) off their hands.

While ambiguous in terms of the actual dimension being measured here, the 7nm node roughly corresponds to the smallest feature measuring 7nm, with one nanometer (=nm) roughly one hundred thousandth the width of a human hair, which sounds cool cause it's really small. Transistors have routinely been made with smaller dimensions, as I routinely made transistors out of carbon nanotubes in grad school (the 1nm node, I suppose), however IBM's got a wafer-full of them here that actually work, not an easy feat, and certainly not something I came anywhere near achieving (nor was trying to).

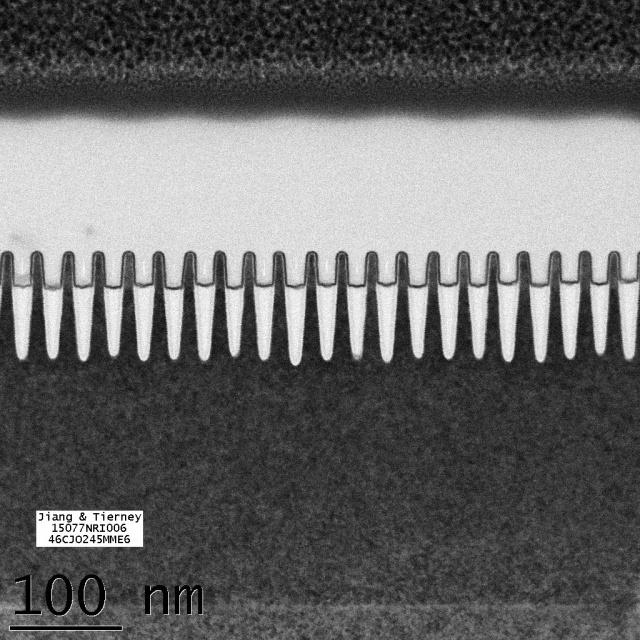

|

| Even-spaced 7nm node transistors, where 7nm corresponds to the tiny spacing between them [IBM Research] |

Moore's Law was christened by Gordon Moore, the original CEO of Intel, who predicted that the number of transistors on a chip would double roughly every 18 months, and has surprisingly proven true over the past 50 years. Very surprising given the amount of technological advancement that had to happen. The flip-side of that prediction is that a Fab would double in price at the same rate, and hence the recent consolidation and divestiture of chip-making plants. Now couple that with Moore's Law running head-first into limits set by physics, and it becomes a big deal.

The delightfully eponymous Patrick Moorhead, a chip technology analyst, said "I believe Intel has done the same thing already [... they're] just not telling people." I'm sure many of my fellow Illinois physics graduates currently employed at Intel's research Fab outside Portlandia are working on said venture, but they won't tell me either. Intel believes the 7nm node will be the last one scalable to wafer-level production with silicon (and to be fair, IBM used an alloy of silicon and germanium).

And it took leaps and bounds just to where we are. Chips are made using optical lithography, akin to old school photography, whereby light-sensitive resists are exposed through a mask, breaking down the resist that's projected through and leaving intact that in the shadows. This gives you feature sizes on the order of the wavelength of light being used, the current industry standard being down in the ultraviolet at 193nm. However, that computer you just bought has chips at the 14nm node, so engineers have done a helluva job squeezing every last bit of resolution out of those photons. As Doug Natelson of Nanoscale Views notes, "[manufacturers] have relied on several bits of extreme cleverness to pattern features down to 1/20 of the free-space wavelength of the light, including immersion lithography, optical phase control, exotic photochemistry, and multiple patterning." IBM made the switch to extreme UV technology (with a wavelength of 13.5nm) to achieve the 7nm node, but of course that came with its own batch of headaches. Those that are particularly painful include powering the laser source and the fact that it's really hard to do optics at that small of wavelength. Which is also why it'll be a few years before the actual manufacturing of these 7nm chips will begin.

It's difficult to predict what happens past the 7nm node, should silicon no longer prove viable. Carbon-based electronics, in the form of nanotubes and graphene, have been much touted for the past decade, but that seems to have fizzled out. Graphene's siblings, silicene, germanene, and black phosphorous, are currently the subjects of ongoing research, as are its wonderful cousins, the similarly thin transition metal dichalcogenides. Different architectures for computing are also in the works as the field of spintronics and magnonics seek to use the spin of the electron to carry information, as opposed to the charge as is done now. And then there's quantum computing, which promises to efficiently solve certain classes of problems, so that's just like different, man.

IBM stock price has dipped $1.84 to $162.01 a share since the announcement.

IBM stock price has dipped $1.84 to $162.01 a share since the announcement.

No comments:

Post a Comment